‘Mom, this pie has jell-o in it. It tastes weird.’

Eloise Granger eased her foot off the accelerator, to see her son’s face screwed up in comical disgust over the remains of his Melton Mowbray pork pie.

The gamey taste and meat jelly was obviously too much of an acquired taste for an American twelve-year-old brought up on meat that had been processed to within an inch of its life. Even for one who had never been a fussy eater she thought, taking in the dimpled skin where Josh’s tummy peeped above the waistband of his ‘husky boy’ shorts.

‘Have some popcorn chips instead then.’

‘I ate all the popcorn chips already,’ Josh whined, his usually sweet nature finally beaten into submission by jetlag and boredom after seven hours in a plane and a total of fifteen hours on the road since they’d left Orchard Habor in Upstate New York yesterday.

‘Once we get to grandma’s, I’m sure they’ll have supper ready.’ Whether it would be edible though was another matter.

If Josh was struggling with the concept of pork pies, what were the chances he would wolf down kale stew or tofu casserole or whatever other vegan weirdness the commune had on the menu tonight?

‘Are we almost there?’ he said.

‘Very nearly.’ The rental car hugged a curve, the high-sided banks on either side of the road topped with wild grass and nettles. The stretch of road was familiar, even if it had seemed never ending too, when she was fourteen and arriving here for the first time with her mum nineteen summers ago. ‘Twenty minutes tops.’

At which point I will get to time-travel back to the worst summer of my life.

So I can top it. And possibly myself in the process.

Why did I ever think running away from Dan and our disaster of a marriage to a place I haven’t been in nineteen years would be a good idea?

The simple answer was, desperation had set in a week ago when Dan had levelled her with his I’ve-just-been-caught-with-my-dick-in-someone-else’s-cookie-jar-again look and told her his latest mistress was accidentally pregnant. And it had all gone downhill from there – because Ellie hadn’t been angry, or upset, or even remotely surprised. She’d just been numb. Numb enough to think that taking her mum up on the invitation she’d been extending to her and Josh for the past four years, ever since Ellie had received that first tentative, white-flag-waving Christmas email from Dee, was a good way of escaping the shit storm that had wrecked her life and her business in Orchard Harbor in less that seven days. Because announcing you were divorcing the town’s Golden Boy was the opposite of good publicity for a woman who made her living as a wedding and events planner. Who knew?

Unfortunately, she hadn’t stopped feeling numb until she and Josh had boarded the plane at JFK… And she’d actually had a moment to contemplate the new shit storm she was flying into.

‘You said that ten minutes ago.’ Josh’s whine drilled through Ellie’s frontal lobe. But she resisted the urge to snap at her son.

He hadn’t complained when she had wrenched him away from everything and everyone he knew, without giving him a proper explanation, and dragged him across an Ocean, not to mention two hundred miles of the M3 and the A303 in a tiny Ford Fiesta because that was the only hire car they had left. And he always got cranky when he was hungry. Right now he was probably ravenous, because she’d had to make do with the limited options at the tiny service station near Tisbury. Hence the Melton Mowbray debacle.

And anyway, even a cranky Josh was a welcome distraction from the flood of memories that had kept her awake during the red-eye flight to Heathrow.

What had she been thinking? That swapping one shit storm for another would somehow cancel them out?

‘I said that less than a minute ago,’ she corrected. ‘But you’re right, that means it’s probably only nineteen minutes now.’

Why was it that when you knew something bad was headed your way, it always took that much longer to arrive? Was it just life’s equivalent of slow-motion replays on America’s Funniest Home Videos? Because she could remember another sunny June day nineteen years ago, when her mum had driven her to Wiltshire, their whole lives packed into the back of the family Range Rover. She had drowned out her mum’s fake cheerfulness by listening to Take That’s break-up album on a loop, and it had taken forever to get there then, too.

‘I’m bored.’ Josh interrupted her maudlin thoughts.

‘Why don’t you play on your DS?’

‘It’s out of charge.’

‘Why don’t you listen to your iPod then?’

‘I’m bored with the songs on it. I’ve listened to them over and over.’ She knew how that felt. After that summer, Robbie and his pals had been dead to her forever.

‘Then have a nap. You must be tired.’ Because I’m exhausted.

Although she doubted she’d sleep anytime soon. All the nervous energy careering round her system made her feel as if she were mainlining coke.

‘Naps are for babies,’ Josh moaned.

‘You’re my baby aren’t you?’

‘Mom!’ She could almost hear Josh rolling his eyes. ‘Don’t say that in front of the new kids, okay. They’ll think I’m weird.’

The smile died as she heard the anxious tone, generated by a year of being the ‘weird kid’ at Charles Hamilton Middle School in Orchard Harbor.

‘They won’t think you’re weird, honey.’

Because I won’t let them.

She didn’t doubt that if the kids at the commune these days were anything like the ones that had been there when she’d arrived at fourteen for that one fateful summer, she’d have a job keeping Josh’s self-esteem in tact.

But she was ready for the challenge. This summer she had no job to go to, or marriage to pretend to care about, giving her ample time to concentrate on the two things she did care about. Her son, and creating a new grand plan to give him the settled, secure, idyllic family life he deserved.

‘Will they think I’m fat?’ Josh asked.

Ellie’s head hurt. ‘No they won’t, because you’re not. Your weight is perfectly healthy.’ Or healthy enough not to risk giving Josh a complex about it with weight charts and unnecessary diets. That’s what the nutritionist had said at any rate, at a cost of two hundred dollars an hour. And at that price, he must have been right.

‘Mom, there’s a sign. Is that it?’

Josh’s shout jogged Ellie’s hands on the steering wheel. She braked in front of the sign, which was no longer a childish drawing of a Rainbow on a piece of splintered plywood, but a swirl of hammered bronze. The sign appeared sophisticated, but it announced the entrance to a rutted track that looked like even more of an exhaust-pipe graveyard than it had nineteen years ago.

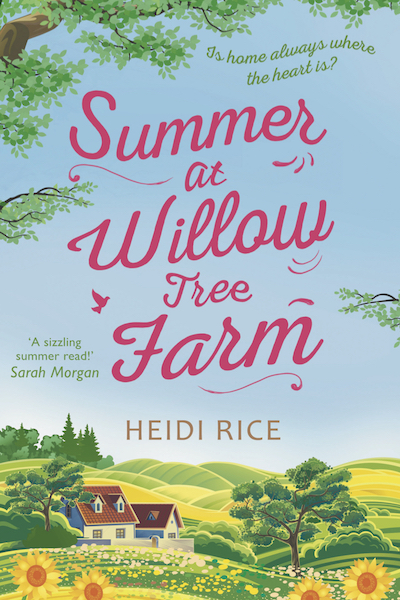

Sunlight gleamed on the metal swirls which read: Willow Tree Organic Farm and Cooperative-Housing Project.

Underneath was another smaller sign listing — shock of shocks — an email address.

So they’d finally managed to dynamite themselves out of the 1960s then. Was it too much to hope the hippies who ran the place even had wifi? Perhaps they’d also realised that calling it The Rainbow Commune had conjured up images of stray dogs and filthy children in badly tie-died clothing? Unfortunately, the state of the track suggested the name change was nothing more than a cynical re-branding exercise.

A Housing Co-Op is probably just a commune in disguise.

Josh bounced in his seat. ‘Let’s go, Mom.’

He sounded so keen, and enthusiastic. How could she tell him this was likely to be a disaster?

Whatever reception she got, Josh was a sweet, sunny, wonderful boy, and anyone who tried to hurt him would have his big bad mother to answer to. Plus they didn’t have to stay, there was still the Madagascar option which she had considered a week ago before settling on Wiltshire.

Ellie crunched the car’s gear shift into first, determined to be positive, no matter what. ‘I’m sure Granny can’t wait to meet you.’

The car bounced down the track, the nerves in Ellie’s stomach bouncing with it like a team of obese gymnasts wearing hobnail boots, as she clung to the one bright spot she’d managed to eek out of her dark thoughts during her night flight.

At least Art Dalton, the scourge of her existence that long ago summer, wouldn’t still be here. Her mother had never mentioned him or his psychotic cow of mother Laura, or even her lover Pam in the letters they’d exchanged in recent years. And Art would be pushing thirty-five. He must have buggered off and gotten himself a life by now– or at the very least, gotten himself arrested.

‘Arthur, they’re nearly here.’ Dee Preston burst round the side of the farmhouse in a swirl of gypsy skirts and jangling bangles brandishing her mobile phone as if it held the Eighth Wonder of the Universe. ‘I got a text from Ellie that she sent from the service station outside Tisbury.’

She grasped Art’s arm. His chopping arm. And the axe thunked into the stubborn trunk he’d been trying to shift all day inches from his boot.

‘Jesus, Dee, calm down.’

Her round, flushed face beamed at him and his heart shrank in his chest. He knew how much Dee had invested in this visit. If Ellie Preston was the same high-maintenance drama queen now she’d been at fourteen, though, he didn’t hold out much hope of Dee getting the Kodak moment she was hoping for with the daughter who hadn’t bothered to come visit her once in nearly twenty years.

‘I almost took off my big toe,’ he added.

‘Stop being such a killjoy.’ Dee shoved the phone at him, only stopping short of inserting it into one of his nostrils by a few millimetres . ‘Read the text and see for yourself. She sent it twenty minutes ago, she should be here any minute.’

Art plucked the phone from her fingers, before he ended up with a nosebleed, and checked the text. He managed to decipher the words “Josh” and “Love Ellie” from the jumble of letters. Without his thirteen-year-old daughter Toto on hand to read it for him properly or the spare time available to decipher each individual word himself and then compile them into a comprehensible sentence, he had to wing it.

‘If she sent it twenty minutes ago, I guess you’re right.’ He handed back the phone. ‘She should be here soon, unless she’s gotten lost.’ And given his present run of shitty luck, that was highly unlikely.

‘You have to come,’ Dee said, grasping his arm. ‘We should welcome them properly, like a community.’

‘You’ve spent the last week redecorating their rooms and the whole weekend baking, isn’t that enough?’ But even as the grumpy words left his mouth, he was being dragged round the side of the house to the front yard, to join the other families who lived on the farm and had already been assembled.

The twin tides of pride and panic assailed him as they always did at the endless get-togethers Dee was always organising to build a sense of community.

Toto was corralling Rob and Annie Jackson’s twin toddlers. Ducks and geese from the nearby millpond roamed over the for-once not too muddy yard, and everyone stood around in small groups. The sunshine glinted off Maddy Grady’s spectacles as she flirted with her boyfriend Jacob Riley. The only two unmarried members of the Project apart from him and Dee, they’d started dating a few weeks after Jacob had come to volunteer for a weekend and then never left. Art shuddered at the memory of the rhythmic thumping coming from Jacob’s room the night before and keeping him awake. Even after close to a year, the shine still hadn’t worn off their sex life, that was for sure.

‘Please smile, Arthur. I don’t want you to scare Ellie when she arrives, like you did the first time.’

‘What do you mean?’ Did Dee know? About the cruel things he’d said to Ellie the night before she’d left that summer? Did she know Ellie wasn’t the only one who’d behaved like a selfish little shit? Guilt coalesced in the pit of his stomach.

‘You ignored her.’ Was that all?

‘Did I?’ Relief coursed through him. Even though that was not the way he remembered Ellie’s original arrival at all. Truth was he’d been fascinated by Dee’s daughter that day. She’d stepped out of her mother’s car, flicked back her Rachel from Friends hair, the pastel silk blouse emphasising the buds of her breasts, and the superior scowl on her face making her look like a fairy queen who’d just swallowed a cockroach.

He’d stared, dazzled by how pretty and pristine she was. And she’d pursed her lips into a brittle smile, wrinkled her nose and looked right through him.

Dee glanced his way, before returning her attention to the road. ‘To a fourteen-year-old girl, when a good-looking boy doesn’t notice you, that’s tantamount to a knife through the heart.’ Dee craned her neck, eager to see round the corner of the barn, her knotted hands a testament to her nerves as she waited for her prodigal daughter’s return. ‘Especially one as vulnerable as Ellie was.’

Vulnerable? Was Dee kidding? Beneath the petite figure and the babydoll face, Ellie Preston had been about as vulnerable as Maggie Thatcher.

‘She didn’t want me to notice her,’ he muttered in his defence. Because she’d done nothing but give him grief when he had.

Dee’s gaze flicked away from the road, the pale blue eyes beseeching. ‘I know you two never did get along. But please, will you try and be nice, or at least not hostile towards her. It would mean so much to me.’

‘Don’t worry, I’m not fifteen anymore,’ he said, trying to keep his voice devoid of tension. ‘And neither is Ellie. I’m sure we can act like grown ups if we put our minds to it.’

And stayed the hell out of each other’s way — which was precisely why he hadn’t planned on being part of the welcoming committee.

‘Ellie runs a very successful event planning business in America, you know,’ Dee said, her voice thick with pride. ‘She might have some ideas that could help with our financial troubles.’

‘We’re not in financial trouble,’ he said, determined to take away the worry lines forming on her forehead.

‘I know it’s nothing you can’t fix,’ she said, reassuring him instead. ‘But maybe Ellie could help you run the place, take some of the burden off your shoulders, while she’s here.’

‘It’s no burden,’ he murmured, thinking of the cramped office he’d escaped from for the afternoon, furnished with a dying Hewlett Packard of indeterminate vintage and floor-to-ceiling shelves bulging with folders full of spreadsheets and order forms and invoices which he had inherited from Dee’s dead partner Pam four years ago — and still hadn’t got to the bottom of.

While he’d have been more than happy to hand the lot of it over to someone else and run like hell, no way could he hand the mess over to Dee’s daughter. As a teenager she’d hated this place with every fibre of her being.

While he might not have the right skills to manage the farm, he wasn’t going to let it be bludgeoned to death by a woman who would happily tap dance on its grave.

‘Don’t worry, I’ll figure out something useful for her to do while she’s here,’ he said wearily, hoping like hell Ellie wasn’t planning to stay for the whole summer.

Maybe Princess Drama could shovel the manure into biodegradable bags? Or collect eggs from Martha, their prime layer, who had a homicidal personality disorder that would rival Caligula? Or better yet, help Jacob set the rat traps in the back barn? If he remembered correctly from the summer he’d spent with Ellie, she had a pathological phobia of mice. And the rats in that barn were big enough to give the farm’s fifteen-pound ginger tom post traumatic stress disorder.

The vice around Art’s ribs loosened as he imagined the many passive aggressive ways he could persuade Ellie Preston to bugger off back to her very successful event planning business in America long before the summer was over.

‘I know you will.’ Dee placed her sun-spotted hand on Art’s forearm. ‘You always know what to do. You’re such a credit to us all.’ She gave his arm a reassuring squeeze, the gesture full of maternal affection. The way she’d begun doing nineteen years ago. The day her daughter Ellie had climbed into her father’s Mercedes and driven away.

He caught the comforting scent of vanilla essence and lavender while Dee nattered about all the exciting things she was going to do with the grandson she’d never met. And his spirits sunk.

Bollocks. He wasn’t going to be able to torture Ellie into leaving without upsetting Dee. The headache at his temple hammered at the base of his skull.

Perhaps he’d be able to sic Martha the psychotic hen on Ellie, but locking her in the barn with the mutant killer rats was probably a non-starter.

‘That’s them,’ Dee’s remark cut into his thoughts.

He lifted his head as a red Ford Fiesta bounded into the yard, then stopped. A boy popped out. About Toto’s height. His short caramel brown hair stuck up in a tuft at the crown. He wore high top sneakers, a grey and blue New York Mets T-shirt, a baseball cap backwards and baggy cargo shorts that slouched on his hips but did nothing to hide his pronounced belly.

‘Hey, I’m Josh,’ he said in a broad US accent. He shuffled his hand in a half-hearted wave that was both eager and shy.

Dee rushed over to gather him close in a hug. ‘Josh, it’s so wonderful to meet you. I’m your Granny Dee.’

The boy smiled, his expression both curious and uncomplicated. And Art spotted the railroad-track braces on his teeth.

Ellie’s kid couldn’t have looked and sounded more like an All-American stereotype if he’d tried. He reminded Art of one of the characters from Recess, the cartoon Toto had devoured like kiddie crack a few years ago.

Ellie stepped out of the other side of the car and Art’s breathing stopped as he absorbed the short, sharp shock of recognition.

In a pair of faded Levis rolled up at the hem and a snug lacy vest top which emphasised her small frame, her wild strawberry blonde hair tied up in a haphazard knot to reveal dangly earrings, she looked summery and sexy and casual, and nothing like the pristine, polished, too perfect girl he remembered. But then Dee placed a hand on her daughter’s arm, and Ellie’s spine stiffened as if someone had shoved a rod up her arse.

Dee began introducing everyone, while the younger kids swarmed round Ellie’s son who seemed astonished by the attention. Toto, like him though, held back.

Then it struck him, as he watched Toto watch the boy, that as the oldest kid here, a card-carrying tomboy and as good as a surrogate grandchild to Dee, his daughter might feel as uncomfortable about the new arrivals as he did. Maybe he should have spoken to Toto about Ellie and her son coming to visit? Was this one of those situations that required the sort of ‘parent-child’ conversation the two of them generally avoided? How was he supposed to know that?

But then Toto stopped watching and marched up to the boy, said something to him and grabbed his hand. The boy’s doughy face lit up as he nodded and allowed himself to be dragged off. Toto in the lead as always like the Pied Piper.

Nope, we’re good.

Thank Christ. This situation was enough of a headwreck already.

Give or take the odd drive-Dad-mad moment Toto was a brilliant kid. Smart, independent, straightforward and unafraid. And like him, she wasn’t the share-and-discuss type.

So yeah, it was all good. No feelings talk required.

Ellie’s body remained rigid as she chatted to her mother, while Mike Peveney and Rob Jackson – who had both bought into the Project with their young families a couple of years ago – set about unpacking her car. A few minutes later they had disgorged enough bags from the two-door compact to spend six months on safari in Kenya rather than a few weeks in Wiltshire.

Digging his fists into the pockets of his work overalls, Art strolled towards the dwindling welcoming party, prepared to follow through on his promise to Dee.

There was no reason why Ellie and he couldn’t be civil to each other. She might not even remember him. Much.

But then his gaze snagged on her strappy top and the way the thin cotton stretched tight across her breasts. The firm nubs of her nipples stood out against the fabric.

He heard a cough, and lifted his gaze. A pair of grass green eyes glared at him. The flush burned the back of his neck, at the thought that he’d just been caught checking her out before he’d even said hello. But then the intriguing tilt at the edges of her eyes went squinty and he noticed the bluish hollows of fatigue underneath.

She looked exhausted.

Her lips pursed and the puddle of pity dried up. The tight smile was as unconvincing as the one nineteen years ago.

‘Hello, Arthur,’ she said, using the name he hated except when Dee used it. ‘You’re still here, then.’

It wasn’t a question, more like a declaration of war.